For the last several months I’ve been working with documentary filmmaker Finn Ryan on an episode of the Field Noise podcast about the noise from F-16 fighter jets over our neighborhood and the public responses to that noise. But as we were gathering material for the story, the Air Force proposed replacing the F-16s with the newer, and much louder, F-35s. Subsequently, Finn and I have found ourselves attending meetings, talking to people and politicians, and, inevitably, taking a side. The clip above is Alder Syed Abbas speaking out against the F-35 at a public meeting on September 12, 2019. And the following newsletter is my attempt to clear up what I find to be some very frustrating sticking points in the public debate about just how loud these new jets will be. Even if you are nowhere near Madison, you might be interested in how the FAA and the Air Force measure jet noise—and what that means for people living around airports.

This month, the city of Madison, Wisconsin, woke up to jet noise. I mean, we wake up to jet noise every day, from the FedEx cargo planes to the commercial flights to the F-16 fighter jets. These jets come in and out of Dane County Regional Airport and nearby Truax Air Force Base, a small but not insignificant airstrip tucked into an area just north and east of our isthmus.

But over the last few weeks, public unease with the sonic impact of a proposal to replace those F-16s with the newer F-35s has evolved from a low murmur into something resembling a full-throated outcry. The Air Force’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), released in August, details significant increases in noise that would occur in the residential areas surrounding the airport. A subsequent analysis by the City of Madison shows that the noise would largely impact lower-income households and people of color. Just in the last week, there has been significant criticism of the plan at both local and federal meetings, alongside, of course, people voicing their support.

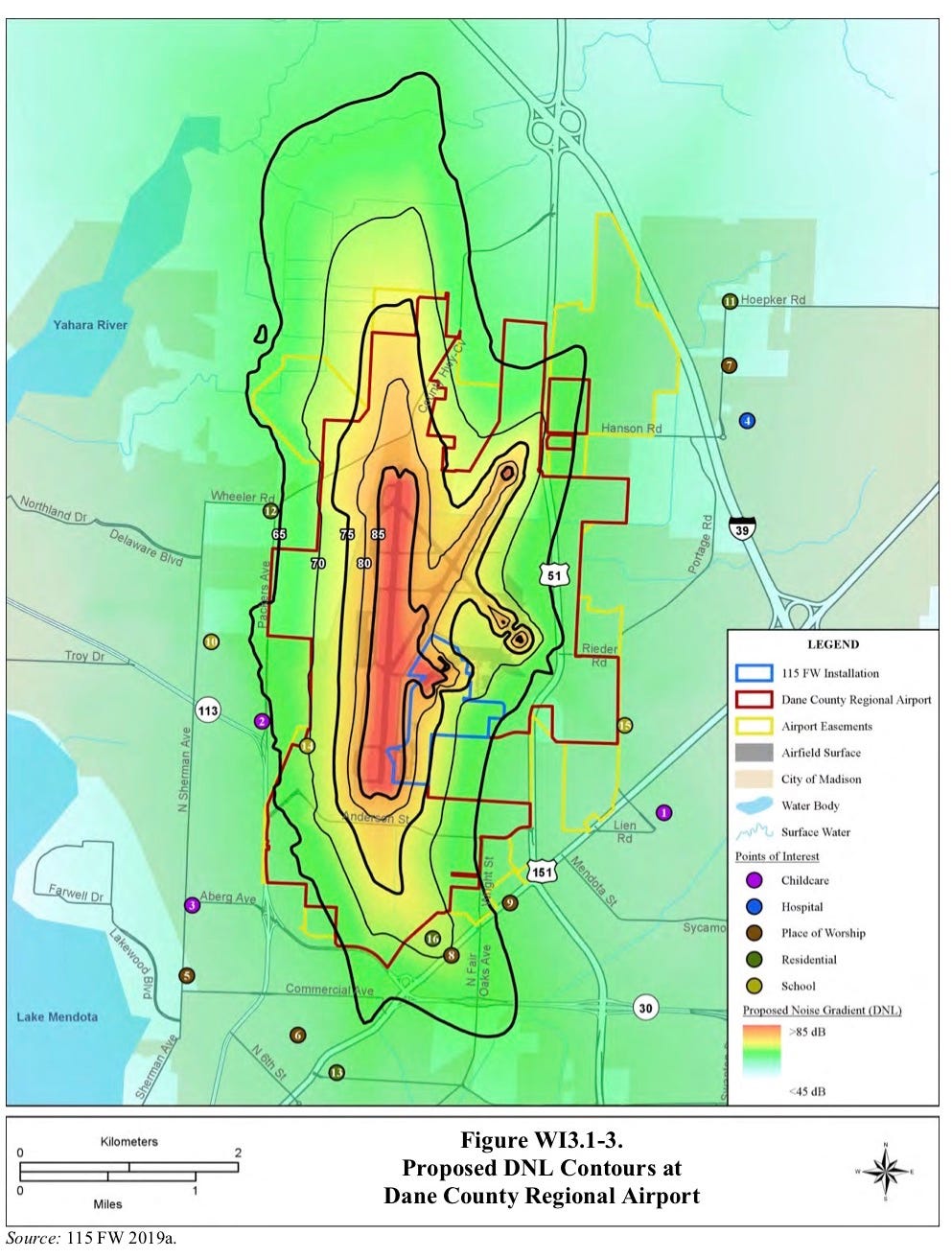

Far from being a hyperlocal problem, the debates here in Madison echo larger issues about the difficulty of measuring, discussing, or even defining noise, especially as it relates to planes. In the case of Madison’s proposed F-35s, the conversation largely centers on a map that appears in several forms in both the EIS and the Madison reports. While some people at the public hearings argued that the map represents a “worst case scenario,” the map is actually—and, perhaps, deliberately—both vague and misleading when it comes to how these jets will actually sound to people in Madison. Spoiler: it’s gonna get loud.

At first glance, the map appears straightforward: there are rings of noise levels moving out from the runways into the surrounding area. These “noise contours” range from over 85 decibels (dB) down to 65 dB and below, with 65 dB being the noise threshold that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) considers “significant.”

But what are we actually looking at here?

First of all, we are looking at a model. Not just because it is predicting possible future noise, but because no noise measurements have ever been taken in this geographic area. Instead, noise made by individual jets (like an F-35, or a Boeing 737) is measured somewhere else, under a variety of conditions, in takeoff, flight, and landing. These measurements are then compiled into a model for that particular aircraft, and then the models for all aircrafts in use at an airport are applied to that airport, based on the daily schedule of actual and proposed flights. That’s how this map was drawn.

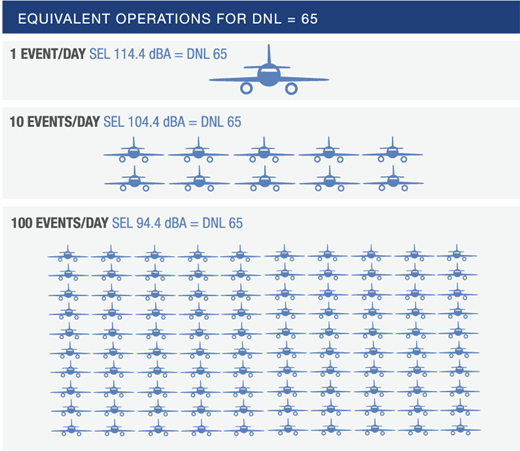

Secondly, we are looking at averages. The scale here is “DNL,” or Day-Night Level, a metric used by the FAA that represents the average noise level over a 24 hour period, in decibels. As the FAA illustrates on their website, there are many ways to arrive at a number like 65dB DNL, ranging from 1 extremely loud thing to 100 (!!) pretty darn loud things:

Thirdly, we are looking at a logarithmic scale. A increase in 10dB actually means a tenfold increase in pressure; an increase of 20db means 100 times as much pressure. Now, decibels are a measurement of air pressure, not perceived volume (a point we’ll return to), which is to say, a difference in 20db will not sound 100x louder to our ears. And to account for this difference, decibels in this instance and many others are “A-weighted,” which is an attempt to account for human hearing. But either way, it means that as this scale goes up, things are getting really, really loud.

What makes the FAA’s use of this scale even more insidious is this graphic comparing jet noise levels to that of household items or everyday experiences:

The Madison news media has pounced on these comparisons, saying in multiple articles that the noise experienced by people living within the 65 dB noise contour would be equivalent to “running a vacuum cleaner.” And in fact, this language is used repeatedly in articles about jet noise, making the noise seem like a minor inconvenience. In one public comment I heard, a man said something like, “I don’t like it when my wife runs the vacuum for a bit during the Packers’ game, but that’s a small inconvenience for our safety.”

But to get to the sound of a vacuum cleaner as an average, his wife would have to run the vacuum not just during the entire game, but all day every day: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Alternately, that same man could experience 100 events per day that are significantly louder than his vacuum cleaner and he would still fall within the 65dB range.

So DNL tells us nothing about the frequency and duration of loud events that people will experience, but it turns out that frequency and duration are two of the most important factors that determine whether or not people find sounds “noisy.” The DNL ignores over 50 years of research in which scientists have observed that volume is not the only metric people use to define noise. By 1966, psychoacoustic researcher Karl Kryter—who spent 10 years as the Director of the Operational Applications Laboratory at the Air Force—could already assert that “the loudness of a sound as defined by physical measurements does not usually correspond with its loudness and noisiness as judged subjectively” [source].

The reasons people consider sounds noisy vary, but include things like what they were doing when they heard it, whether they were home or at work, what their job is, whether they were awake or asleep, how long the sound went on, whether or not they have an emotional or personal connection to the sound, and more. In other words, noise is human and cultural, not—or certainly not only—the province of scientific modeling and decibel measurements. One person’s music can be another person’s noise.

It’s tempting, then, to dismiss noise as an individual problem—but in fact it is and always has been a collective one. Even Karl Kryter could see that: “It is a matter of equities. This factor cannot be judged on a scientific basis; it is a matter of opinion concerning the rights of individuals to be protected from nuisances, and the welfare of the community as a whole.”

It’s been interesting to hear Madisonians speak out for the welfare of our communities this week. Will the Air Force listen?

Stay tuned for “The Sound of Freedom” on this season of the Field Noise podcast, and be sure to follow Field Noise on Instagram for short videos of sounds in the world.

Share this post